Atlantic Ocean circulation at weakest point in 1,600 years

by The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution 17 Apr 2018 11:50 UTC

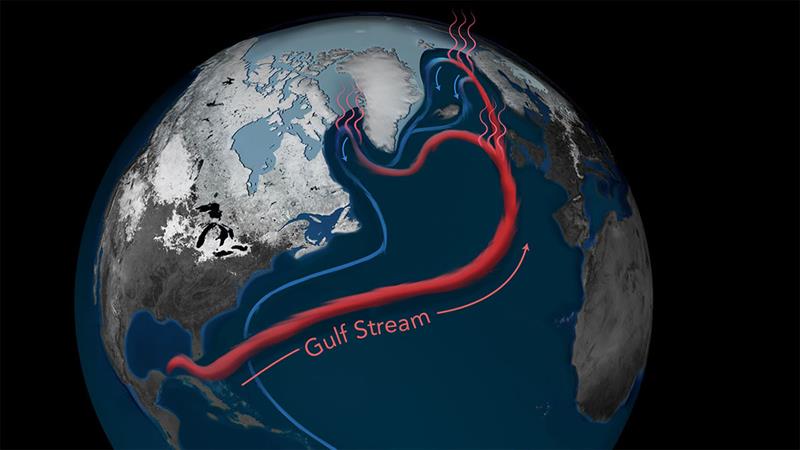

The North Atlantic is a key juncture in the world ocean circulation system that has impacts on our climate. The Gulf Stream carries warm, salty water to the Labrador Sea and the Nordic Seas, where it releases heat to atmosphere and warms Western Europe © Natalie Renier, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

New research led by University College London (UCL) and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) provides evidence that a key cog in the global ocean circulation system hasn't been running at peak strength since the mid-1800s and is currently at its weakest point in the past 1,600 years. If the system continues to weaken, it could disrupt weather patterns from the United States and Europe to the African Sahel, and cause more rapid increase in sea level on the U.S. East Coast.

When it comes to regulating global climate, the circulation of the Atlantic Ocean plays a key role. The constantly moving system of deep-water circulation, sometimes referred to as the Global Ocean Conveyor Belt, sends warm, salty Gulf Stream water to the North Atlantic where it releases heat to the atmosphere and warms Western Europe. The cooler water then sinks to great depths and travels all the way to Antarctica and eventually circulates back up to the Gulf Stream.

"Our study provides the first comprehensive analysis of ocean-based sediment records, demonstrating that this weakening of the Atlantic's overturning began near the end of the Little Ice Age, a centuries-long cold period that lasted until about 1850," said Dr. Delia Oppo, a senior scientist with WHOI and co-author of the study which was published in the April 12th issue of Nature.

Lead author Dr. David Thornalley, a senior lecturer at University College London and WHOI adjunct, believes that as the North Atlantic began to warm near the end of the Little Ice Age, freshwater disrupted the system, called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). Arctic sea ice, and ice sheets and glaciers surrounding the Arctic began to melt, forming a huge natural tap of fresh water that gushed into the North Atlantic. This huge influx of freshwater diluted the surface seawater, making it lighter and less able to sink deep, slowing down the AMOC system.

To investigate the Atlantic circulation in the past, the scientists first examined the size of sediment grains deposited by the deep-sea currents; the larger the grains, the stronger the current. Then, they used a variety of methods to reconstruct near-surface ocean temperatures in regions where temperature is influenced by AMOC strength.

"Combined, these approaches suggest that the AMOC has weakened over the past 150 years by approximately 15 to 20 percent" says Thornalley.

According to study co-author Dr. Jon Robson, a senior research scientist from the University of Reading, the new findings hint at a gap in current global climate models. "North Atlantic circulation is much more variable than previously thought," he said, "and it's important to figure out why the models underestimate the AMOC decreases we've observed." It could be because the models don't have active ice sheets, or maybe there was more Arctic melting, and thus more freshwater entering the system, than currently estimated.

Another study in the same issue of Nature, led by Levke Ceasar and Stefan Rahmstorf from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, looked at climate model data and past sea-surface temperatures to reveal that AMOC has been weakening more rapidly since 1950 in response to recent global warming. Together, the two new studies provide complementary evidence that the present-day AMOC is exceptionally weak, offering both a longer-term perspective as well as detailed insight into recent decadal changes.

"What is common to the two periods of AMOC weakening – the end of the Little Ice Age and recent decades – is that they were both times of warming and melting," said Thornalley. "Warming and melting are predicted to continue in the future due to continued carbon dioxide emissions."

Oppo agrees, both noting, however, that just as past changes in the AMOC have surprised them, there may be future unexpected surprises in store. For example, until recently it was thought that the AMOC was weaker during the Little Ice Age, but these new results show the opposite, highlighting the need to improve our understanding of this important system.