Major shift in marine life occurred 33 million years later that thought

by British Antarctic Survey 21 May 2018 01:43 UTC

Major shift in marine life occurred 33 million years later © British Antarctic Survey

A new study of marine fossils from Antarctica, Australia, New Zealand and South America reveals that one of the greatest changes to the evolution of life in our oceans occurred more recently in the Southern Hemisphere than previously thought. The results are published today (17 May 2018) in the journal Communications Biology.

The Marine Mesozoic Revolution (MMR) is a key theory in evolutionary history. While dinosaurs ruled the land, profound changes occurred in the shallow seas that covered the Earth.

During the Mesozoic, around 200 million years ago, marine predators evolved that could drill holes and crush the shells of their prey. And although small in comparison to dinosaurs, these new predators, including crustacea and some types of modern fish, had a dramatic impact on marine life.

Among the species most heavily affected were sea lilies or isocrinids – invertebrates tethered to the seafloor by graceful stalks. Side on, these stalks resemble a vertebral column; in cross section, they are shaped like a five-pointed star – because sea lilies are related to starfish, sea urchins, and sand dollars. At their height during the Paleozoic, forests of sea lilies carpeted seafloors the world over.

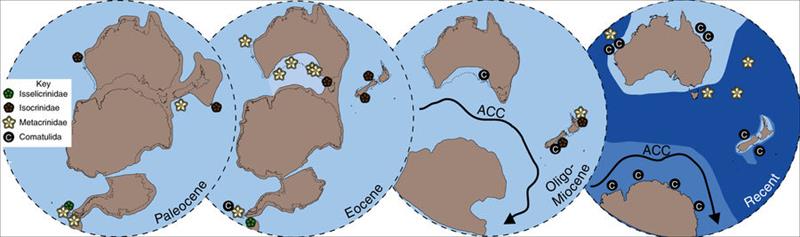

Their restricted ability to move made sea lilies vulnerable to the new predators, so during the MMR they were forced into deeper waters in order to survive. Because it marked such a radical change in marine communities, scientists have long sought to understand this shift. They believed it had occurred by 66 million years ago, but this new study shows that in the Southern Hemisphere, sea lilies remained in shallow waters until much more recently – around 33 million years ago.

A team from British Antarctic Survey, the University of Cambridge, the University of Western Australia, and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Victoria, made the discovery when they brought together field samples from Antarctica and Australia, with fossils from museum collections for the first time. The study provides conclusive evidence that this change happened at different times in different parts of the globe, and in the Antarctic and Australia, sea lilies hung on in shallow waters until the end of the Eocene, around 33 million years ago and it is unknown exactly why.

The study shows that knowing more about the Antarctic can reshape – or overturn – existing scientific theories.

According to lead author Dr Rowan Whittle from British Antarctic Survey:

"It is surprising to see such a difference in what was happening at either end of the world. In the Northern Hemisphere these changes happened whilst the dinosaurs ruled the land, but by the time these sea lilies moved into the deep ocean in the Southern Hemisphere the dinosaurs had been extinct for over 30 million years.

"Given how the ocean is changing and projected to change in the future it is vital that we understand how different parts of the world could be affected in different ways and at a range of timescales."

To get this richer picture of how sea lilies responded to the changing oceans of the Southern Hemisphere over millions of years, the team travelled to some of the remotest regions of Western Australia and Antarctica. Their hunt for fossil sea lilies was rewarded by the discovery of nine new species.

Co-author Dr Aaron Hunter from the University of Cambridge says: "We have documented how these sea lilies evolved as Australia split away from Antarctica moving north and becoming the arid outback we know today, while ice formed over the South Polar Region.

"The sea lilies survived in the shallow waters for millions of years longer than their Northern Hemisphere cousins, but as the continents moved further apart, they eventually had nowhere to go but the deep ocean depths where they have clung on to existence to this day".

Read the paper here.