New research reveals full diversity of Killer Whales as two species come into view on Pacific Coast

by NOAA Fisheries 31 Mar 17:59 UTC

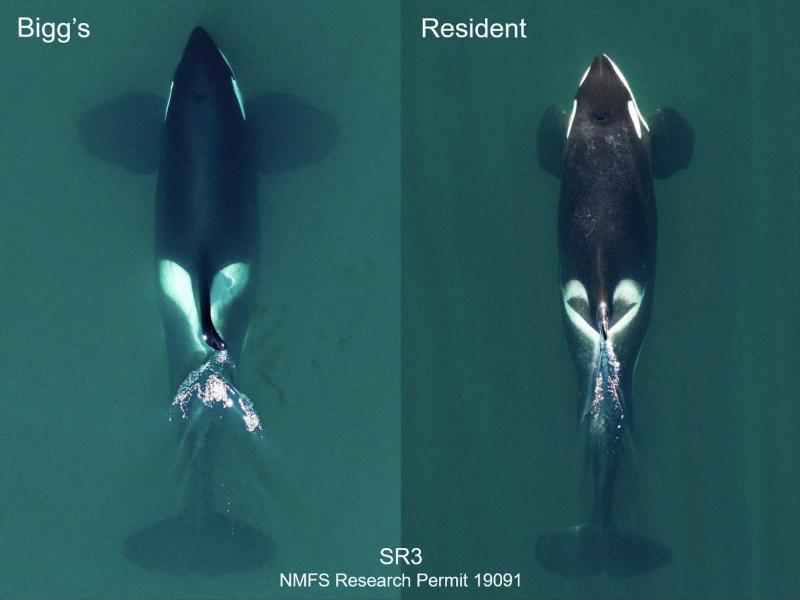

Aerial images comparing sizes of adult male Bigg's and Resident killer whales, both taken in the Salish Sea off southern Vancouver Island. Images are scaled to lengths calculated during health research by SR3 SeaLife Response, Rehabilitation and Research © John Durban and Holly Fearnbach

Long viewed as one worldwide species, killer whale diversity now merits more.

Southern Resident Connections - Post 35

Scientists have resolved one of the outstanding questions about one of the world's most recognizable creatures, identifying two well-known killer whales in the North Pacific Ocean as separate species.

Killer whales are one of the most widespread animals on Earth. They have long been considered one worldwide species known scientifically as Orcinus orca, with different forms in various regions known as "ecotypes."

However, biologists have increasingly recognized the differences between resident and Bigg's killer whales. Resident killer whales maintain tight-knit family pods and prey on salmon and other marine fish. Bigg's killer whales roam in smaller groups, preying on other marine mammals such as seals and whales. (Killer whales actually belong to the dolphin family.) Bigg's killer whales, sometimes called transients, are named for Canadian scientist Michael Bigg, the first to describe telltale differences between the two types.

He noted in the 1970s that the two animals did not mix with each other even when they occupied many of the same coastal waters. This is often a sign of different species.

The finding recognizes the accuracy of the listing of Southern Resident killer whales as a Distinct Population Segment warranting protection under the Endangered Species Act in 2005. At the time, NOAA described the distinct population segment as part of an unnamed subspecies of resident killer whales in the North Pacific.

Now a team of scientists from NOAA Fisheries and universities have assembled genetic, physical, and behavioral evidence. The data distinguish two of the killer whale ecotypes of the North Pacific Coast—residents and Bigg's—as separate species.

"We started to ask this question 20 years ago, but we didn't have much data, and we did not have the tools that we do now," said Phil Morin, an evolutionary geneticist at NOAA Fisheries' Southwest Fisheries Science Center and lead author of the new paper. "Now we have more of both, and the weight of the evidence says these are different species."

Genetic data from previous studies revealed that the two species likely diverged more than 300,000 years ago and come from opposite ends of the killer whale family tree. That makes them about as genetically different as any killer whale ecotypes around the globe. Subsequent studies of genomic data confirm that they have evolved as genetically and culturally distinct groups, which occupy different niches in the same Northwest marine ecosystem.

"They're the most different killer whales in the world, and they live right next to each other and see each other all the time," said Barbara Taylor, a former NOAA Fisheries marine mammal biologist who was part of the science panel that assessed the status of Southern Residents. "They just do not mix."

Recognizing New Species

The Taxonomy Committee of the Society of Marine Mammalogy will determine whether to recognize the new species in its official list of marine mammal species. The committee will likely determine whether to accept the new designations at its next annual review this summer.

The scientists proposed scientific names for the new species based on their earliest published descriptions in the 1800s. Neither will keep the ubiquitous worldwide moniker, orca. The team proposed to call resident killer whales Orcinus ater, a Latin reference to their dominant black coloring. Bigg's killer whales would be called Orcinus rectipinnus, a combination of Latin words for erect wing, probably referring to their tall, sharp dorsal fin.

Both species names were originally published in 1869 by Edward Drinker Cope, a Pennsylvania scientist known more for unearthing dinosaurs than studying marine mammals. He was working from a manuscript that California whaling captain Charles Melville Scammon had sent to the Smithsonian Institution describing West Coast marine mammals, including the two killer whales. While Cope credited Scammon for the descriptions, Scammon took issue with Cope for editing and publishing Scammon's work without telling him. (See accompanying story.)

The Smithsonian Institution had shared Scammon's work with Cope, and a Smithsonian official later apologized to Scammon for what he called "Cope's absurd blunder."

Species Reflect Ecosystem

The contested question of whether Southern Residents were distinct enough to merit endangered species protections initially drove much of the research that helped differentiate the two species, said Eric Archer, who leads the Marine Mammal Genetics Program at the Southwest Fisheries Science Center and is a coauthor of the new research paper. The increasing processing power of computers has made it possible to examine killer whale DNA in ever finer detail. He said the findings not only validate protection for the animals themselves, but also help reveal different components of the marine ecosystems the whales depend on.

"As we better understand what makes these species special, we learn more about how they use the ecosystems they inhabit and what makes those environments special, too," he said.

The new research synthesizes the earliest accounts of killer whales on the Pacific Coast with modern data on physical characteristics. The team also use aerial imaging (called photogrammetry), and measurement and genetic testing of museum specimens at the Smithsonian and elsewhere. While the two species look similar to the untrained eye, the evidence demonstrates they are very different species. The two species use different ecological niches, such as specializing in different prey, said Kim Parsons, a geneticist at the NOAA Fisheries Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle and coauthor of the new research.

Recent research with drones that collect precise aerial photos has helped differentiate Bigg's killer whales as longer and larger. This might better equip them to go after large marine mammal prey. The smaller size of residents is likely better suited to deep dives after their salmon prey, said John Durban, an associate professor at Oregon State University's Marine Mammal Institute. His killer whale drone research is done collaboratively with Holly Fearnbach, a researcher at SR".

The different prey of the two species may also help explain their different trajectories. Southern Residents are listed as endangered in part because of the scarcity of their salmon prey. Bigg's killer whales, by contrast, have multiplied while feeding on plentiful marine mammals, including California sea lions.

While killer whales represent some of the most efficient predators the world has ever seen, Durban said science is still unraveling the diversity among them. The identification of additional killer whale species is likely to follow. One leading candidate may be “Type D” killer whales identified in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica.

Other killer whales in Antarctic waters also look very different from the best-known black and white killer whales. This reflects a wider diversity within the species, said Durban, who has used drones to study killer whales around the world. "The more we learn," he said, "the clearer it becomes to me that at least some of these types will be recognized as different species in due course."

Lost Skulls and Latin: How scientists chose names for newly identified Killer Whale species

A California whaler sent his manuscript to the Smithsonian, but it ended up elsewhere.

Southern Resident Connections - Post 34

The scientist who first named different species of killer whales on the West Coast of North America probably never saw one.

The Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution had invited Edward Drinker Cope to review a manuscript the Smithsonian had received from a California whaling captain named Charles Melville Scammon. A brilliant and ambitious young scientist from Pennsylvania, Cope would later become famous for naming more than 1,000 species and digging—and fighting over—dinosaur fossils across the American West.

Scammon's manuscript described several large marine mammals of the West Coast, calling killer whales "the wolves of the ocean," which he said lived "by violence and plunder." He identified two species, distinguishing them according to their dorsal fins. One species had tall, sharp dorsal fins, he observed; the other had shorter, blunt dorsal fins. He called them "high- and low-finned orcas."

A team of NOAA Fisheries and university scientists published new research in Royal Society Open Science showing that West Coast resident and Bigg's killer whales are different species.They are the first separately identified species of killer whales, breaking from the longstanding view that all killer whales belong to one worldwide species.

The father of species classification, Carl Linnaeus, in 1758 described killer whales as the single species Delphinus orca, later moved to the genus Orcinus. Other scientists have since claimed to have identified other species. However, the claims were sometimes based on only a single skeleton and lacked enough detail to be accepted by the science community. The descriptions of the two new species are based on hundreds of specimens, with detailed comparisons of genetic and other data.

To identify names for the new species, the scientists dug into the history of killer whale science on the Pacific Coast. They learned of lively personalities, evolving taxonomy, and missing skulls.

Cope Published Scammon's Work

The Smithsonian may have intended Cope merely to review Scammon's manuscript but Cope edited and then published the manuscript in the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia in 1869. He credited Scammon for the descriptions in the manuscript and listed himself as editor. But Cope never advised Scammon before publishing it, according to a 1986 biography of Scammon called, "Beyond the Lagoon." While the descriptions of the species in the publication came from Scammon, the first species names for killer whales came from Cope.

He named one species Orca rectipinna (=Orcinus rectipinnus), a Latin term for "erect wing," referring to the tall, sharp dorsal fin. He named the whales with shorter fins Orca ater (=Orcinus ater), Latin for black, referring to their dark color.

There is no record that Cope ever conducted research at sea or saw a live killer whale.

Cope and Scammon may, in many cases, have been distinguishing only male and female killer whales that they thought represented different species. Scientists now recognize that the largest male killer whales usually have the largest, sharpest dorsal fins. Lower and more blunt fins are typical for females and young males.

"The descriptions and illustrations make it clear that Scammon and Cope were not paying attention to the fine details that allow present-day biologists to distinguish the two species," the new research paper reports. There is no sign, for instance, that they realized that Bigg's killer whales (also called transients) prey on marine mammals while resident killer whales eat fish.

Scammon and Cope "were on the right track with two species, but they did not have all the details," said Tom Jefferson, a research scientist at NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fisheries Science Center and coauthor of the new research separating resident and Bigg's killer whales into different species. He probed archives and early accounts of Scammon's whaling exploits for clues as to possible names.

Jefferson and his coauthors proposed to adopt Cope's scientific names for the two species, assigning Orcinus ater for residents and Orcinus rectipinnus for Bigg's killer whales. That means neither species will carry the ubiquitous name orca, derived from the worldwide species name, Orcinus orca.

Scammon was not pleased when he found out that Cope had edited and published his manuscript, in large part because he called Scammon a "United States Marine." In fact, he had joined the Revenue Marine Cutter Service, a predecessor of the U.S. Coast Guard. Scammon sent letters to the Smithsonian, and Smithsonian Secretary Spencer Baird apologized for what he called "Cope's absurd blunder," according to the Scammon biography.

Whaling Across the Pacific

Scammon became an early authority on whales and other marine mammals while hunting them throughout the eastern Pacific Ocean.

He grew up in Maine with the fortuitous middle name "Melville," although he was born before Herman Melville wrote his masterwork Moby Dick. Scammon sailed for the West Coast at 24, captaining a ship full of settlers seeking their fortune in the California Gold Rush around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America. He then took up whaling, and turned out to be very good at it. While hunting whales, he observed and recorded their behavior. He discovered one of the large inland lagoons in Baja California, Mexico, where gray whales often give birth and nurse their calves. It is still known today as "Scammon's Lagoon."

Scammon killed and examined a 15-foot female killer whale in California thought to be a Bigg's, as it had seal carcasses in its stomach. The whale's skull is believed to have been deposited at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. It was the obvious skull to be the "holotype" specimen used to define its species. Usually, the holotype is the first collected specimen of a species. However, the Academy's entire collection including the skeleton and associated written records were destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire.

Since that first suspected Bigg's skeleton was lost, Jefferson and his colleagues identified a stand-in skull from the Smithsonian Institution collected near San Francisco in 1966. It served as the "neotype," a substitute that can define the species if the original is missing. They did the same for the resident species, Orcinus ater, with a skull collected in Puget Sound in 1967.

Despite the new scientific names, the scientists suspect that most people will continue to refer to them as residents and either transients or Bigg's killer whales. They hope to engage with Northwest tribes to identify an appropriate common name for resident killer whales that recognizes their cultural importance to many West Coast tribes.